Long before modern countries like China and Dubai began making artificial islands, the Calusa people built a kingdom on seashells.

Artificial islands may seem like a modern oddity, devised by China to claim territory or by Dubai to lure tourists. But people have been building them for centuries, using a mix of rocks and other materials to make new land rise from the sea.

One interesting example lies off southwest Florida, where the Calusa — a Native American people who once dominated the area — used hundreds of millions of seashells to create an island city near today’s Fort Myers Beach. It was one of many fishing villages the Calusa built, but it grew into a major political hub, spanning 125 acres, rising 30 feet high and housing an estimated 1,000 people. And as a new study shows, this island evolved along with the complex society that made it.

Now known as Mound Key, it served as capital of the Calusa kingdom when Spanish explorers first arrived in 1513. Calusa warriors eventually chased off the invaders, but conquistadors had already introduced diseases for which the native people had no immunity. Their society eventually came to an end around 1750, and Mound Key was later “frequented by pirates and fishermen,” according to Florida State Parks, before homesteaders took over and sold it to a utopian cult in 1905. Finally, in the 1960s most of Mound Key was protected as a state park.

Hoping to unearth secrets about Mound Key and the Calusa, a research team led by University of Georgia archaeologist Victor Thompson decided to dig a little deeper with core samples, excavations and intensive radiocarbon dating. Their work, published April 28 in the journal PLOS One, reveals how the makeup of Mound Key changed over the centuries in response to both social and environmental shifts.

“This study shows peoples’ adaptation to the coastal waters of Florida, that they were able to do it in such a way that supported a large population,” Thompson says in a statement. “The Calusa were an incredibly complex group of fisher-gatherer-hunters who had an ability to engineer landscapes. Basically, they were terraforming.”

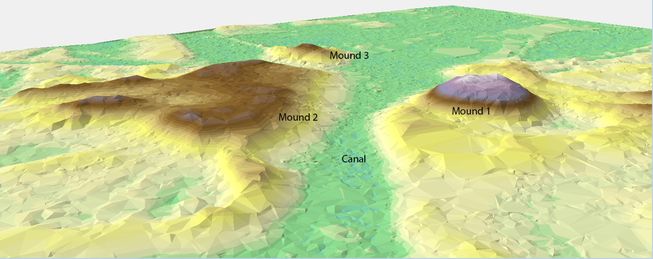

A model of Mound Key earlier in its history, before the central channel was filled in. (Photo: Kai Schreiber/Flickr)

A model of Mound Key earlier in its history, before the central channel was filled in. (Photo: Kai Schreiber/Flickr)

Walking on seashells

Mound Key was created mostly from piles of seashells, bones and other discarded objects — collectively known as “midden” in archaeological parlance. It likely began as a flat, mangrove-lined oyster bar that didn’t quite poke above the shallow waters of Estero Bay, according to Florida State Parks, but the Calusa transformed it by using seashells like bricks and muddy clay as mortar.

Normally, midden piles are like vertical timelines, with newer materials covering progressively older stuff underneath. On Mound Key, however, Thompson and his colleagues found many older shells and charcoal fragments above younger ones. That suggests the Calusa were reworking their midden deposits to make landforms, the researchers say, and kept shaping them for various reasons over time.

“If you look at the island, there’s symmetry to it, with the tallest mounds being almost 10 meters (32 feet) high above modern sea level,” Thompson says. “You’re talking hundreds of millions of shells. … Once they’ve amassed a significant amount of deposits, then they rework them. They reshape them.”

Thompson suspects the Calusa abandoned Mound Key during times of low sea levels and scarce fish, then returned when climatic conditions and fishing became favorable again. Their large-scale labor projects gave the island its final shape during a second major occupation, and seem to have been supported mainly by fishing. They might have even stored live surplus fish at Mound Key, Thompson adds.

Fallen leaves aren’t enough to hide the pile of shells that push Mound Key above the ocean. (Photo: Kai Schreiber/Flickr)

Fallen leaves aren’t enough to hide the pile of shells that push Mound Key above the ocean. (Photo: Kai Schreiber/Flickr)

Conch kingdom

The Calusa controlled most of South Florida in the 16th century, and aside from being fierce fighters, they were also expert anglers. Many native people in Florida farmed, but the Calusa typically only grew small garden plots. Men and boys made palm-tree nets to catch fish, spears to catch turtles and fish-bone arrowheads to hunt deer, while women and younger children caught conchs, crabs, clams, lobsters and oysters.

This lifestyle was surprising to the Spanish, Thompson explains, whose agricultural society almost immediately clashed with the “fisher kings” of Mound Key.

“They had a fundamentally different outlook on life because they were fisher folk rather than agriculturalists, which ultimately was one of the great tensions between them and the Spanish,” Thompson says. “If you think about the way in which you interact with people, it is dependent on your history, and it’s the same with any society. So the Calusa’s long-term history really structured the way those interactions with the Spanish went.”

Two University of Georgia students excavate a site on top of Mound 1 at Florida’s Mound Key. (Photo: Victor Thompson/UGA)

Two University of Georgia students excavate a site on top of Mound 1 at Florida’s Mound Key. (Photo: Victor Thompson/UGA)

Based on what they’ve learned through excavations and core samples, Thompson and his colleagues have begun to rethink many previous ideas about how this society emerged and evolved. Researchers who study the Calusa should pay more attention to the context of environmental change, they say, something they’ve already been studying at another important Calusa site known as Pineland.

“Pineland was the second largest of the Calusa towns when the Spaniards arrived,” says study co-author William Marquardt, of the Florida Museum of Natural History. “Our research there over more than 25 years has provided an understanding of how the Calusa responded to environmental changes such as sea-level rises. They lived on top of high midden-mounds, engineered canals and water storage facilities, and traded widely while developing a complex and artistic society. It takes a team of scientists with different skills working together to discover how all this worked.”

It also takes more than one study. Thompson, Marquardt and the rest of the team are returning to Mound Key this month for phase two of their research. Although the Spanish described the Calusa as warlike, closer study is revealing an astute society that had sophisticated ways to deal with shifting sea levels and food availability.

“There’s a whole story that goes along with this site,” Thompson says. “It’s a laboratory that allows us to explore many different things, some of which are important to the present and the future and some of which are important to understanding the past.”

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.