A team of researchers affiliated with the Warsaw University Observatory has captured for the first time the events that led to a classical nova exploding, the explosion itself and then what happened afterwards. In their paper published in the journal Nature, the team describes how they happened to capture the star activity and why they believe it may help bolster the theory of star hibernation.

The nova, named Nova Centauri 2009, exploded back in 2009, but by happenstance, the research team had been monitoring the same part of the sky while working on another project. When they noticed the explosion, the researchers went back and studied the images they had obtained earlier to build a progressive timeline.

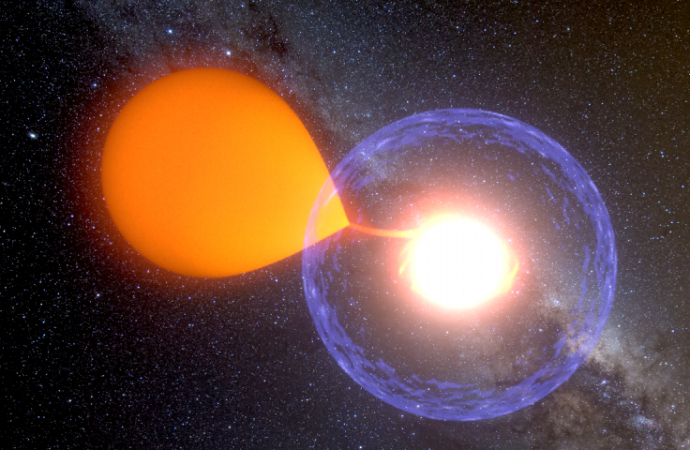

A classical nova, unlike a supernova, does not result in the star being destroyed; instead, material it had been collecting from its nearby companion is burned off in a thermonuclear explosion. In this case, the nova was part of a binary star system made from white and red dwarf stars—material from the red dwarf was slowly transferred to the white dwarf until it reached a tipping point, causing the explosion. Studying what had transpired prior to the explosion, the researchers were able to see fluctuations in brightness, indicating mass being transferred up to just six days before the explosion. They were also able to see that the rate of mass transferred to the white dwarf increased dramatically immediately after the explosion. They report also that the increase in brightness due to the explosion is still visible, though it is diminishing.

The observation of the events surrounding the explosion has bolstered the theory that such events also include hibernation periods, the researchers suggest—because they were able to observe periodic brightening and dimming over a six-year period prior to the explosion. Hibernations, as their name implies, are periods during the life of a binary system during which very little activity occurs. It also implies that the events are cyclical, with explosions occurring repeatedly over millions of years. As researchers continue to monitor the binary, they will be looking for a drop in the mass transfer rate, which would offer more credence to the theory.

Source: Phys.org

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.