The 2016 Nobel Prize in chemistry has been awarded for the design and synthesis of the world’s smallest machines. The work has overtones of science fiction, but holds huge promise in fields as diverse as medicine, materials and energy.

All grand endeavours start small.

This is especially true of efforts to develop nano-scale machines (1,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair), which are always destined to remain tiny however big our ambitions for them grow.

It’s difficult to trace the development of molecular machines to one person or scientific step.

But a 1959 lecture by the celebrated physicist Richard Feynman is as good a point as any.

His talk, given at an American Physical Society meeting in California and titled Plenty of Room at the Bottom, laid the conceptual foundations for nanotechnology.

In it, he also anticipated one of the most widely discussed applications for molecular machines – in nano-robotic surgery and localised drug delivery.

“Although it is a very wild idea, it would be interesting in surgery if you could swallow the surgeon,” Feynman told the audience.

“You put the mechanical surgeon inside the blood vessel and it goes into the heart and ‘looks’ around. It finds out which valve is the faulty one and takes a little knife and slices it out.”

This concept didn’t take long to appear in science fiction, including the 1966 film Fantastic Voyage, in which a submarine crew are miniaturised and injected inside the body of a scientist in order to save him.

Fifty years on, we haven’t succeeded in turning this particular fiction into reality. But the promise is still very much alive. It is hoped, for example, that tiny mechanical delivery systems could one day be injected into the body to deliver toxic chemotherapy drugs directly to the tumour, without harming healthy tissues.

But, as one of the three 2016 chemistry laureates, Sir Fraser Stoddart, told the BBC: “This doesn’t happen overnight; it takes a very long time and hundreds of very talented postdocs.”

At the time Richard Feynman was thinking about manipulating matter at tiny scales, chemists were already laying the groundwork.

In the 1950s and 60s, they were trying to link chemical ring-shapes together in chains, in a bid to come up with new advanced molecules. But early progress faded as scientists struggled to produce enough of these molecules to justify the complex methods.

In 1983, a French research group led by Jean-Pierre Sauvage – another of this year’s trio of laureates – made a significant step forward.

Sauvage meshed two molecules together around a central copper ion, forming the first link in a chain. Using this method, the French team was able to increase the yield substantially on previous attempts to create linked molecules.

Fraser Stoddart moved the field on when he synthesised a nano-scale rod with stoppers at the end – called a dumbell – and wrapped a ring-shaped molecule around it.

“The ring can be made to move back and forth between two sites. You have an on switch and an off switch and the switch can be built up into a machine,” Sir Fraser explained.

These molecules, known as rotaxanes, have been the basis for a variety of nanomachines produced by Sir Fraser and his colleagues.

These have included a nano-lift, which can raise itself 0.7 nanometres above a surface, and a tiny artificial muscle, where rotaxanes bend a thin lamina made of gold.

“We’ve worked hard to find practical applications in molecular electronics,” added Sir Fraser.

Working with Jim Heath at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), he set about developing a tiny computer chip. Moore’s Law predicts the doubling of transistors on electronic circuits every two years or so.

But there has been speculation that the law might be reaching its limits, so molecular transistors could offer a way of extending the growth of processing power in our electronic devices.

“By 2007, we had a 160 kilobit memory. The only problem with it is it is not robust. Today we’re looking at how we can increase the longevity of the switches,” Sir Fraser told the BBC.

“We have just recently submitted a paper for publication on this topic, so that’s still very much alive.”

The third laureate, Ben Feringa, from the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, developed the first molecular motor – considered a landmark in this field.

Normally, molecules’ movements are governed by chance; on average, a spinning molecule moves as many times to the right as to the left. But in 1999, using a series of clever molecular tricks, Prof Feringa and his colleagues succeeded in designing a molecule that would spin in a particular direction.

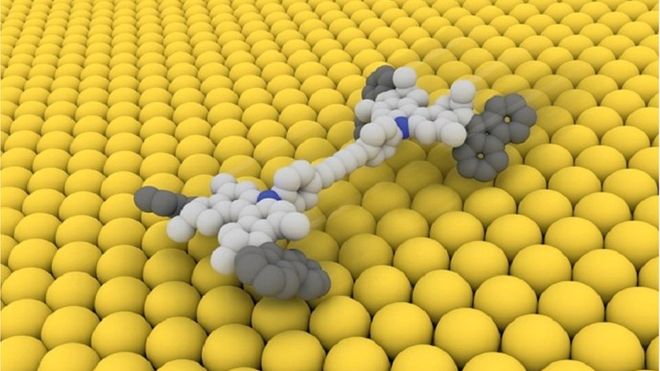

In 2011, they put this to use by building a four-wheel-drive “nanocar”: consisting of a molecular chassis which held together four motors functioning as wheels. Spinning the wheels drove the tiny automobile forward across a surface.

Today, many other teams are building on and extending the work of the last five decades. In 2013, a team led by David Leigh at the University of Manchester built a nano-robot that could grab amino acids – the building blocks of proteins – and connect them – just like the ribosomes in our cells.

These remain lab-based demonstrators, but researchers foresee potentially game-changing applications in the real world.

“The world is so aware of the Nobel Prizes and they influence the research. It will make the area blossom; more scientists will move into the area and it will attract more funding. You can expect the applications to appear much more rapidly now,” Prof Donna Nelson, president of the American Chemical Society (ACS), told the BBC News website.

Drugs could be activated to work in the body using a molecular switch, and then inactivated via the same mechanism. This could be advantageous in the case of cancer treatments, which are harmful to healthy tissues; and where antibiotics have to be used.

“One of the biggest challenges these days is fighting antibiotic resistance developing in bacteria,” said Tibor Kudernac, who completed his PhD under the guidance of Ben Feringa, and is now an assistant professor at the University of Twente in the Netherlands.

“This could be one way – to activate the antibiotics only for transient amounts of time when they need to be active in our bodies. But by the time they leave our bodies, they would already be inactive.”

Another use might be in light-driven molecular actuators, which convert energy into mechanical motion. These could have uses in the field of soft robotics, which eschews metals for lightweight, flexible materials.

“If you need to manipulate fragile or sensitive objects – including humans’ internal organs in the future – you don’t want a robotic arm grabbing on them. You would rather have a very soft touch. Molecular-based systems are ideal for these kinds of future applications,” Dr Kudernac told the BBC News website.

A longer-term aim is to mimic some of the biological machinery inside the cell, such as that used when cells divide.

This could potentially find uses in the burgeoning discipline of synthetic biology, which aims to redesign life, or even build artificial organisms.

“One of the main characteristics of life is cellular division. We would really like an artificial cell that can self-divide,” said Dr Kudernac.

“We have no idea how to do this in synthetic systems, so that is the next challenge. We can use these artificial cells to learn how life came about, but also to synthesise complicated chemical compounds.”

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.