Titan, one of Saturn’s moons, is probably the best option to sustain life for future generations.

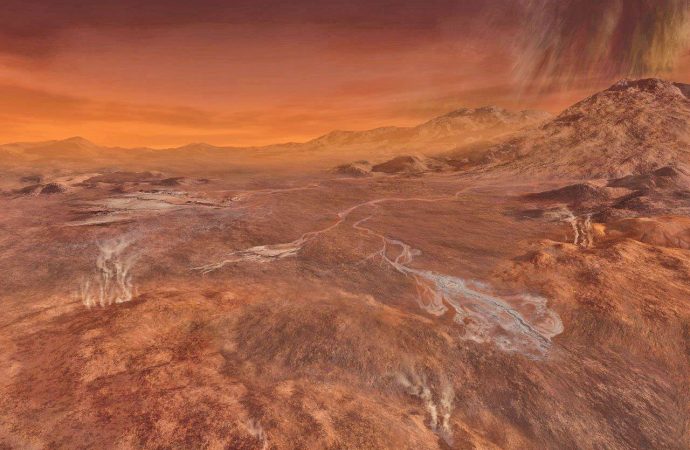

It’s several hundred years in the future. You live in a cold climate, but thick clothing keeps you warm. You eat food from the community greenhouse. Sometimes you even go boating, spending tranquil days under the orange sky. Life is similar in some ways to how it is now. In other ways, it’s very different.

For one thing, you can fly.

Also — your body is now permanently incapable of adapting to Earth’s atmosphere, and you can never return.

This is life on Titan, the largest of Saturn’s more than 50 moons.

The scenario isn’t as outlandish as you think. According to Charles Wohlforth and Amanda R. Hendrix, Ph.D., the authors of “Beyond Earth: Our Path to a New Home in the Planets” (Pantheon Books), Titan will be the most natural place for Earthlings in the future, rather than the more commonly known alternative, Mars.

Science, they say, has found that Mars will likely remain uninhabitable. Titan, however, could be surprisingly adaptive for humans fleeing planet Earth because of a global war, natural disaster, decimation of our resources or other unseen events.

The authors note that Mars once had “large bodies of water” and a rain-producing atmosphere. But that’s gone now, replaced by “peroxide-like chemicals toxic enough to sterilize the surface of any life similar to what we know on Earth,” most likely due to electrons from the sun that destroyed its atmosphere.

Other planets have been investigated as well. For a time, scientists were optimistic about Venus, a heavenly body sometimes referred to as “Earth’s twin.” But information gathered by the Mariner 2 spacecraft in 1962 found the planet’s surface to be “hotter than a baking oven,” with an average surface temperature of 870 degrees Fahrenheit.

“[The planet’s] atmosphere is much too thick, much too hot, and contains corrosive sulfuric acid, and the winds at high altitudes are ferocious. At the surface, the atmosphere is as heavy as the deep sea on Earth. Human beings couldn’t go there.”

The planet Mercury, meanwhile, is the “weirdest and least appealing to visit” of the “four rocky inner planets” (along with Earth, Venus and Mars), as it’s “tiny, lacks an atmosphere, and is dominated by its close proximity to the sun.”

But while the closest planets hold little hope for colonization, Titan — which is seven years away from Earth — has many factors that could more easily sustain human life.

When NASA’s Cassini probe, which arrived at Saturn in 2004 and will continue sending information throughout next year, flew over Titan, it found “something that looked smooth, like a lake,” with “branching shapes that looked exactly like the channels, bays, and coves of a shoreline on Earth.” At certain points, the sunlight glinting off the lake “looked exactly like afternoon light reflecting off lake waters on Earth.”

While Titan has “the only surface liquids in the solar system other than Earth,” there are, of course, significant differences as well.

“Its enormous lakes hold many more hydrocarbons than have ever been discovered on our planet,” the authors write. “Cassini’s gravitational measurements suggest that a slushy ocean of water lies within Titan, but the clouds, rain, rivers and lakes on the surface are liquid ethane and methane, like the contents of liquefied natural gas tankers. Titan has weather, beaches, and tides, but it is colder than a deep freeze.”

Given our familiarity with ethane and methane, “Titan’s landscape is buried in fuel we could harvest and burn with technology hardly more advanced than the gas furnace found in a typical American house.”

Titan’s atmosphere is “mostly nitrogen, like Earth’s but without oxygen,” the lack of which would make both burning fuels and breathing impossible.

But beneath the surface, Titan’s mass is made up of “water ice or slush,” which contains plenty of oxygen. Its water ice can be run through an electrical field, powered by a small nuclear reactor, to release the water. This process, called electrolysis, is how astronauts breathe aboard the International Space Station.

“The colonists [on Titan] could also breathe it,” the authors write, “and could use it to burn methane, which would provide plenty of energy.”

The power unleashed by burning the methane and oxygen, therefore, could power all life on Titan, including farming.

“With Titan power plants running on hydrocarbon fuels, colonists could build large, lighted greenhouses to grow food and process the carbon dioxide exhaust from fuel combustion back to oxygen.” They could create plastic with the resources on hand, and mine nearby asteroids for metals.

The authors cite Ralph Lorenz of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, who has written several books about Titan, as saying that it’s a place where “human beings could survive without space suits, walking around in warm clothes and oxygen masks, and could live in nonpressurized buildings.”

While the temperature is excessively cold — around minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit — “clothing with thick insulation or heating elements would keep you comfortable.”

One odd effect of Titan’s atmosphere, which is 50 percent greater than Earth’s with air four times as dense, is that “people can fly with very little difficulty in Titan’s low-gravity environment.”

‘The body changes shape as organs float upward in the chest cavity to new positions, and weight releases from joints.’

Titan, which is 50 percent larger in diameter than our own moon, has less gravity than it — in fact, it has just “14 percent of the gravity of the Earth.” Winged suits would allow people to “effortlessly glide great distances,” and even the smallest bit of propulsion, from “flapping wings attached to your arms” to “an electric-powered prop,” would enable full-on human flight.

Of course, this is all a long way off. For one thing, no human has ever traveled that far, and current signs show that even if we devise a way for people to do so, spaceflights of that length could have devastating consequences.

Astronauts aboard the International Space Station (ISS), for example, experience physical changes to their bodies.

“The body changes shape as organs float upward in the chest cavity to new positions, and weight releases from joints,” the authors write.

“Astronauts get taller, their waists contract and their chests expand. The brain is the most flexible of all, reprogramming itself to create its own frame of reference in a three-dimensional world without up or down.”

But while astronauts physically adapt in a way that caused astronaut Mike Barratt to comment, “We kind of turn into extraterrestrials,” the further into space we go, the more those changes will be unhealthy.

Sixty percent of astronauts who have endured long space flights have developed sometimes irreversible vision issues including “reduction of vision sharpness or blind spots,” thought to be caused by “constantly increased fluid pressure in the brain caused by weightlessness.” The authors note that while most ISS astronauts only fly six months at a time, longer missions, such as a proposed three-year mission to Mars, could cause “partial blindness.”

There are also concerns about possible effects of space on the human brain that haven’t been discovered yet, including increased risks of cancer or dementia.

From a practical standpoint, life in deep space would create other challenges. For one, weightlessness and diminished gravity would affect both sex in space and the development of any children born there.

While no studies on sex in space have been officially conducted, we do know it has happened, according to “insiders at the Johnson Space Center.” Apparently, “the fluid shift of weightlessness produced unwanted and even painful erections for some astronauts.” This weightlessness would also make copulation a challenge, as “without gravity, it would be difficult to create the right forces for penetration and thrusting.”

Assuming this problem was solved, weaker gravity could have dire consequences for children born in this atmosphere.

“Human reproduction may not work without full Earth-strength gravity,” the authors write.

“Environmental influences on developing brains and bodies can be permanent. Weak gravitational forces or weightlessness could shape children in drastically different ways … conception may require gravity. The placenta might not attach correctly.”

Even if ways are found to solve all these problems, children raised in a low-gravity environment would have bones and hearts too weak to handle Earth’s atmosphere — they could most likely never travel to our planet.

Given the number of variables, any consideration of a permanent human colony in space — which would certainly require procreation to advance the new civilization — is a long way off.

Cassini is scheduled to crash into Saturn, vaporizing the craft, late next year, and no follow-up mission is currently scheduled.

Still, even if you, your children, and possibly your grandchildren are doomed to spend your lives Earth-bound, your descendants will “go boating on lakes of liquid methane and fly like birds in the cold, dense atmosphere [of Titan], with wings on their backs.”

Source: New York Post

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.