The legend of the Wild Man is alive and well and transforming remote villages in northwest China into booming tourist towns.

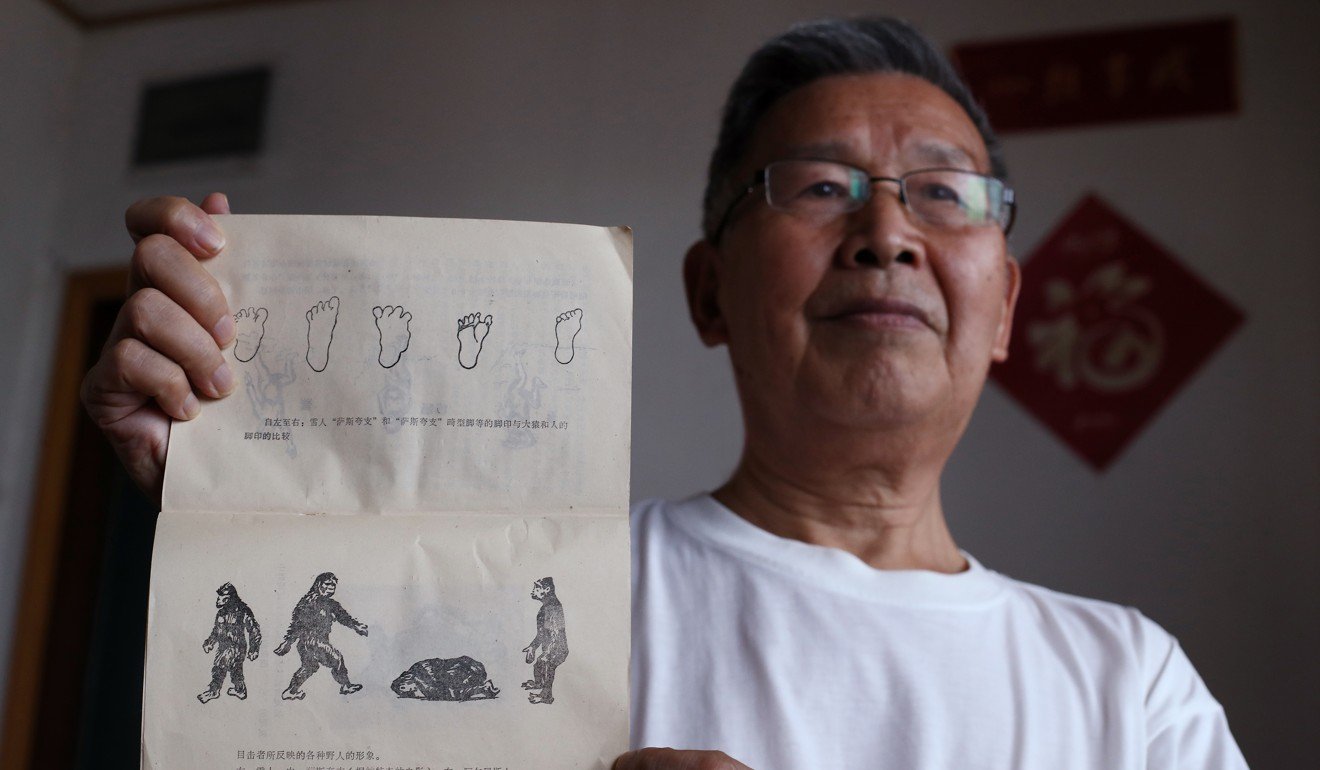

It was nearly 40 years ago, but Yuan Yuhao remembers his brush with “China’s answer to Bigfoot” like it was yesterday.

“It was about 3 o’clock in the afternoon,” the former soldier recalled of the day in 1981 when his expedition in northwest Hubei province was interrupted by the sight of a “black-red humanoid animal, walking upright” on a sunny mountain slope.

“Its speed was very fast, but it was walking, not running,” Yuan said. As the creature ranged across a mountain in Fang county, bordering the Shennongjia Forestry District, “it walked faster than a human ran”.

Yuan quickly loaded his rifle and took dead aim at the figure. But before he could pull the trigger, his colleague intervened.

“Don’t you dare shoot!” Yuan recalled his colleague saying. “If you do and it turns out to be a human you’ve wounded or killed, and not a yeren, then what will happen?”

The beast continued up the peak and disappeared behind a cliff, according to Yuan.

Like the fabled Sasquatch of North American folklore and the mythical yeti, or Abominable Snowman, of the Himalayas, the legend of the yeren – meaning Wild Man – is alive and well in Shennongjia.

LIVING LEGEND

A Unesco World Heritage Site famed for its stunning karst mountain landscapes and dense evergreen forest, Shennongjia’s largely unspoilt environment and varied microclimate make it home to many rare and protected species, including giant pandas, clouded leopards and golden snub-nosed monkeys.

But public fascination with the legendary yeren – an apelike being said to live in the wilderness and leave behind large footprints – has been a boon for the area, transforming formerly remote rural villages into booming tourist towns.

Described as over 2 metres (6 feet, 5 inches) tall and covered in thick red fur, resembling a hybrid between an ape and a human, the Wild Man has reportedly been sighted more than 400 times in the last century in Shennongjia and the surrounding counties.

Its legend in China dates back 2,000 years, featuring in ancient poems such as Qu Yuan’s Mountain Spirit and the Classic of Mountains and Seas – testimony, some say, to the human need to believe in the existence of a larger-than-life denizen of the wild.

A spate of yeren sightings in the 1970s and 1980s brought nationwide attention to the phenomenon, leading to a large-scale, state-backed expedition in 1977.

But this and successive quests by researchers and enthusiasts have failed to unearth any conclusive evidence of the creature’s existence – apart from mysterious giant footprints, strange stools and red-coloured fur samples that have not been DNA-tested.

Claims to the contrary have been staunchly debunked over the years by scientists at universities in Wuhan and Beijing, who dismiss so-called eyewitness accounts as unreliable hearsay from rural, often uneducated witnesses.

But a group of older men – many of whom are local, and know the area well – have spent most of their lives hunting for evidence to prove the yeren does, in fact, exist.

INTO THE WILD

Yuan Yuhao, 70, said he initially did not believe in the creature when he was recruited for the 1977 state expedition; but he became a believer, he said, after his first yeren sighting during an expedition in 1981.

The figure he swears he saw that day was about 2.2 metres tall, since its head was visible above the surrounding bamboo forest.

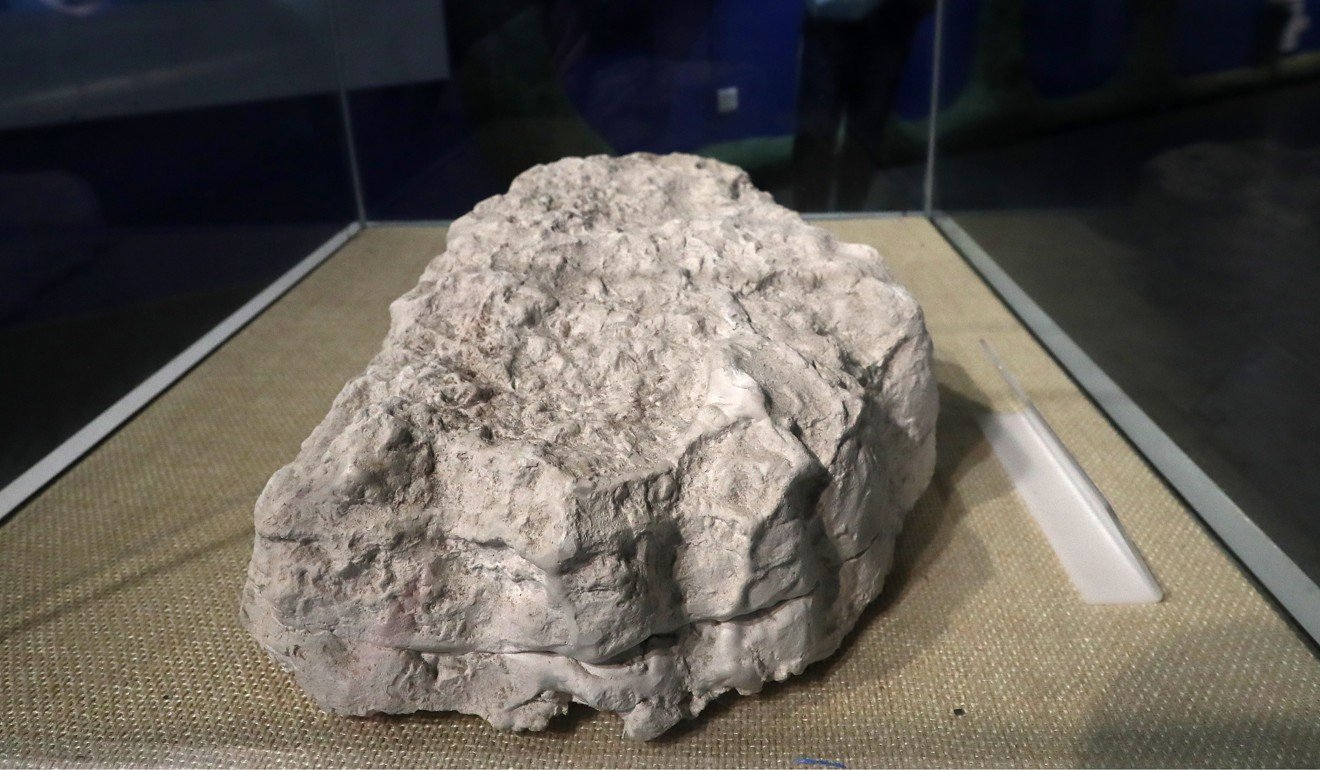

Although Yuan found no yeren footprints or hair at the scene, he made a plaster cast of a giant 40cm footprint he found in a nearby forest that year, believing it came from the same “species”.

The footprint, about twice the size of a human print, remains in Yuan’s possession to this day.

“I’ve seen all of Shennongjia’s wild animals, and there are none I don’t recognise,” said Yuan, who grew up in the area and still lives there.

“Bears and golden snub-nosed monkeys cannot walk more than three to five steps on their hind legs,” he said, disputing the claim that the footprint could have been made by a known animal.

Li Guohua, 68, became similarly captivated by the yeren legend after coming to Shennongjia to work as a lumberjack in 1972. He claims he glimpsed the creature five times between 1980 and 2005, including once in February 1980 while on a solo research expedition.

“I sat on a cliff to rest after hauling my equipment,” he said. “Suddenly, I heard footsteps and saw a yeren walking towards me. It was very tall, at least 2.5 metres, taller than the tallest human. It was about 60 metres away.”

Li said he then whipped out his gun and aimed it at the creature.

“I was looking at the yeren with all my concentration and it was likewise staring at me,” he said.

“I tried to target its lower body, since I wanted to injure it so it could not walk. But as soon as I pulled the trigger, I missed my target. I fired again and again, but did not hit it.”

The being turned and fled, leaving a trail of footprints in the snow as Li unsuccessfully pursued it, he said.

Since then, Li has dedicated his life to solving the mystery of the yeren. He now spends several months a year living out of a makeshift hut in the mountains, frequently risking his life by venturing outside in harsh conditions.

Li blames scientists for hampering the effort to prove the creature’s existence by dismissing the testimony of local people who, he said, had actually seen it.

“Academics have said that it was just baseless rumours believed by common people who could not understand science, and their attitude has continued to this day,” he said.

“These so-called scientists who call themselves yeren experts could sit at home drinking a single cup of tea for a lifetime and proclaim one sentence to deny the existence of yeren: that they don’t believe in it.”

Eyewitnesses had come from all walks of life, he said, including tourists, students, soldiers and even Communist Party cadres.

The latter were behind the most influential sighting in 1976, which spurred the 1977 government-funded expedition.

CLOSE ENCOUNTER

Chen Liansheng, 71, was then a high-ranking local government official who purportedly had an encounter with a strange creature on a remote forest road in Shennongjia while travelling back from a work conference.

At about 4am on May 14, 1976 he and his five colleagues were awakened by their driver shouting that something on the road was ahead of them.

“The driver stopped about a metre away from the animal,” Chen said. “Three of us in total got out of the car – it was so near that we could touch it.”

The startled creature froze for a moment in the glare of the headlights as the driver beeped the horn a few times.

“It was covered in red fur,” he said. “Its face human-like, with upright ears and a protruding mouth. Its eyes did not reflect light, like human eyes.

“Its arms were thin but its lower half was very thick like a cow, and it didn’t have a tail.

“We had never seen anything like this in a zoo. It wasn’t a cow or a bear.”

One of Chen’s colleagues threw a stone at the beast, but it leapt across a ditch and disappeared into the shrubbery.

The next day, Chen, who later became a Hubei Television journalist, filed a report about the incident with the Chinese Academy of Sciences and notified the local government.

When he returned to the spot, he found around 20 bright red hairs, all of which were subsequently donated to museums or researchers, or lost.

But a lack of concrete evidence – namely yeren bones, fossils, bodies and corpses – has continued to undermine his cause.

HAIRS OUT OF PLACE

Hair samples believed to have belonged to yeren were identified as wild boar hair, tree fibres and even dyed human hair, according to a 2012 research paper by palaeontologist Zhou Guoxing of the Beijing Natural History Museum.

Zhou, who took part in several previous yeren research expeditions, also concluded that footprints believed to have been made by the Wild Man were likely to have been bear tracks.

Palaeoanthropology expert Wu Xinzhi of the Chinese Academy of Sciences backs Zhou’s conclusions, saying Shennongjia does not have suitable environmental conditions for the continued survival of this “species”.

“If those who possessed yeren hairs were genuinely confident that it existed, they would submit them for DNA testing,” he said.

“If they were found not to be an existing species of ape or another animal, then I would believe in yeren. But I have not heard of any tests or definitive results in this regard.”

This consensus, however, has not stopped the Shennongjia Forestry District government from using yeren to promote various tourism projects; an entire museum dedicated to yeren research is complemented by a striking 10-metre tall statue representing a yeren mother and child at the Guanmenshan Scenic Area.

Tour companies offer “yeren discovery” packages, and various restaurants in the forestry district’s main town of Muyu proudly feature yeren in their signage.

Visitor traffic in the area, which is a national nature reserve, was recently capped at 798,000 visitors per year to limit environmental damage.

LIFE’S WORK

But for Wang Shancai, chairman of the Hubei Yeren Research Society, digging up proof of the mythical creature’s existence will remain his life’s work. The retired Hubei Cultural Relics Institute archaeologist lives in the provincial capital of Wuhan, far from his family in Shanghai, solely to continue his research.

The society he established in 2009 now has around 200 members, many of whom claim to be eyewitnesses, including Chen, Li and Yuan.

Denied government funding for their endeavour because of official doubts of the existence of yeren, the society desperately is seeking help to conduct a major expedition using hi-tech equipment such as motion sensors, infrared cameras and drones.

“I have spent the past 21 years doing this,” said Wang, who claims to have poured at least 700,000 (US$100,100) of his savings into yeren research.

“I’m now 82 years old. If I live for a few years then I might as well do research for a few more years. I’ve sacrificed a lot for this cause.

“At this age, I should be relaxing with my family.”

Instead, his greatest wish is to attract more people and funding to the movement, so they can help determine once and for all whether these mythical creatures exist.

Large areas of Shennongjia’s 3,200 sq km of forests are yet to be explored, and Wang said he believed this unique area could hold more secrets.

“We cannot say with certainty that we have discovered all the animals that exist on Earth,” he said. “This is a huge mistake.”

Source: South China Morning Post

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.